Implicit Bias

Structural racism and discrimination in education have been well documented. Less research exists about the intersectionality of disability and other social identities such as race and gender. However, this topic is crucial to our understanding of the dynamic within ICT Classrooms.

One of the reasons that the intersectionality of disability and other social identities is less researched may be that within the educational systems, decision-makers who usually have a lot of discretion often believe that they are acting objectively based on facts. However, research shows that implicit biases—that is, attitudes or stereotypes that affect our understanding and actions in an unconscious manner—exist in all aspects of education and disability diagnosis (identification, placement, and discipline).

Racial Implicit Bias and Disability Diagnosis

Watch: Why Is Disability Representation So White?

Watch: Why Is Disability Representation So White?

(Note: The presenter speaks quickly, particularly during a montage within the video. You can press the settings icon on the bottom right-hand corner of the screen to choose a slower playback speed.)

Racial bias and white supremacy can lead to misdiagnosis, over-diagnosis of specific types of disabilities, and under-diagnosis of others. Read more about white supremacy culture in this article.

Studies have shown that Black and other minority students are

- more likely to be misdiagnosed;

- more likely to be educated in restrictive environments as opposed to the least restrictive environment called for by the Individuals With Disabilities Act (IDEA);

- likely to be over-diagnosed in high-incident categories of disability (which are more subjective) and under-diagnosed in low-incident categories (which are more objective).

The disproportionately high number of Black students with subjective disability diagnoses versus objective diagnoses is a clear indicator of how implicit bias can factor into a student’s disability diagnosis.

Gender Bias and Disability Diagnosis

In another example of implicit bias playing out in diagnoses, research shows that women have often been excluded from medical research and are frequently misdiagnosed. A common example of this is the under-diagnosis of autism in women, connected to a lack of research.

“The percentage served under IDEA who received services for autism was higher for male students (13 percent) than for female students (5 percent).”

—National Center for Educational Statistics

Author Maya Dusenbery spoke at the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine Conference about the impact of implicit bias on women’s health stemming from two major gaps: a “knowledge gap” and a “trust gap.” In the article “Women More Often Misdiagnosed Because of Gaps in Trust and Knowledge,” Liz Seegert shares Dusenbery’s ideas from the conference. Dusenbery explained, “There’s a general lack of knowledge about women’s symptoms, bodies, and conditions that disproportionately affect them. That’s the legacy of decades of women being underrepresented or excluded from the research.”

Dusenbery went on to note that “there’s a lack of trust in women’s self-reports about what they’re experiencing, and a tendency to dismiss or psychologize complaints. That is part of the broader cultural stereotypes about women, and in particular, the conflict of hysteria, whose explanations ranged from a ‘wandering womb’ to demonic possession to witchcraft. Once Freud entered the picture at the end of the 19th century, hysteria became a catch-all psychological explanation for these unexplained complaints, which manifested as physical symptoms.”

Implicit Bias and Consequences in the Classroom

There are also consequences once students have been diagnosed. For example, there is a high rate of students with diagnosed disabilities being suspended and expelled.

“Nearly 75 percent of special education students were suspended or expelled at least once.”

—Dustin Rynders, “Battling Implicit Bias in the IDEA to Advocate for African American Students With Disabilities”

Keeping in mind that during the 2018–19 school year, more than seven million students in the United States of America received special education services, we can begin to sense the grand scale of implicit bias and lack of awareness of how intersectionality can impact students with disabilities in ICT classrooms. Often the implicit biases held by classroom educators and administrators can compound upon one another, which can have consequences beyond students’ K-12 education.

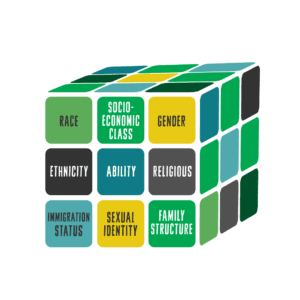

Going back to the analogy of the Rubik’s Cube, consider that this resource has only cited very briefly how implicit biases often play out in diagnosis and treatment with two of so many possible identities.

Learn

Learn Reflect

Reflect Explore

Explore